A low white blood cell count can feel like a silent alarm. Nothing looks different in the mirror, yet your body’s defenses are running short-staffed. If you’re in Cancer treatment, newly diagnosed, or even in remission and still coming in for labs, this can be one of the most unsettling parts of the whole experience.

It also asks something of you that’s easy to overlook. Courage, not the loud kind, but the steady kind. The kind that shows up in small choices, made over and over, even when you’re tired.

This guide is general, not personal medical advice. Your oncology or hematology team’s instructions come first, especially if you’ve been told you have neutropenia or you’re on a special diet or prevention plan.

Low white blood cell count during cancer care: why it matters

White blood cells are part of your immune system, and one group (neutrophils) acts like the everyday security team. They’re often the first to respond when bacteria get in. When neutrophils drop, your risk of infection rises, and infections can get serious faster than you’d expect.

A low white blood cell count can happen for many reasons in Cancer care, including chemotherapy, certain targeted therapies, radiation, immunotherapy, or after a stem cell transplant. Sometimes the dip is brief and predictable, sometimes it’s stubborn. Either way, the goal is the same: prevent infection and catch problems early.

One tricky thing is that neutropenia often doesn’t “hurt.” You might feel normal until you don’t. That’s why clinics talk so much about temperature checks and quick calls. Fever can be the first, and sometimes the only, early sign.

If you want a clear explanation of what neutropenia is and why fever matters, Memorial Sloan Kettering’s patient handout is a solid reference: neutropenia and low white blood cell count.

Here’s the hard truth and the hopeful truth at the same time: you can’t control every germ, but you can control your habits. That’s where everyday courage lives.

What to avoid and what to do while your count is low

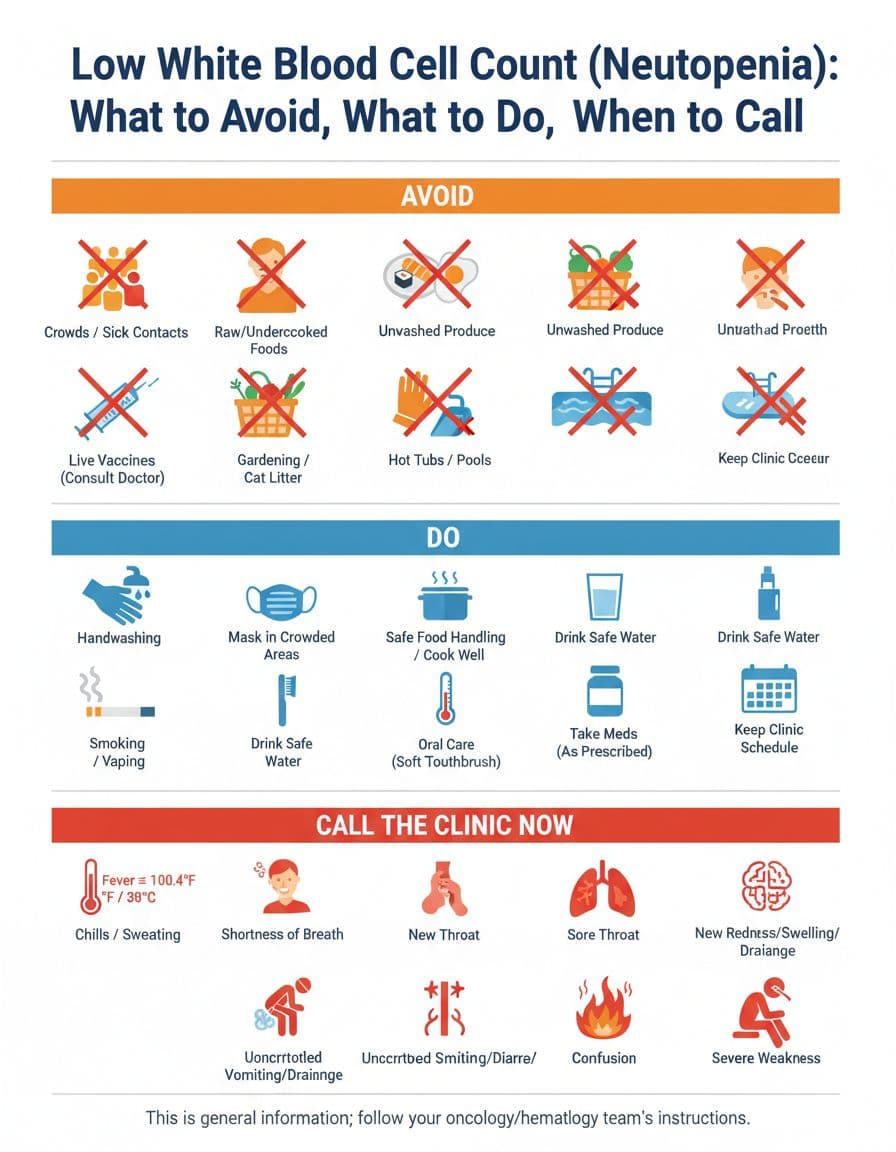

What to avoid (think: fewer chances for germs)

Avoiding certain things isn’t about fear. It’s about lowering the number of “germ encounters” your body has to handle while it’s short on defenders.

Sick contacts and crowded indoor spaces: Skip close contact with people who are coughing, feverish, or “just getting over something.” If you have to be in a crowd, ask your team about masking and timing errands for quieter hours.

Raw or undercooked foods: Sushi, runny eggs, rare meats, and unpasteurized foods can carry bacteria. When your counts are low, food safety stops being a nice idea and becomes protection.

Unwashed produce: Rinse fruits and vegetables well. If your clinic recommends avoiding raw produce entirely during severe neutropenia, follow that plan.

Soil and stagnant water: Gardening, potting soil, and cleaning up after pets (especially litter boxes) can expose you to organisms you don’t want right now. Hot tubs and poorly maintained pools can also be risky.

Smoking and vaping: Beyond long-term harm, they can irritate your airways, and irritated airways are easier to infect.

For more detail on practical precautions during neutropenia, the CDC’s patient page is clear and level-headed: CDC guidance on neutropenia infection risk.

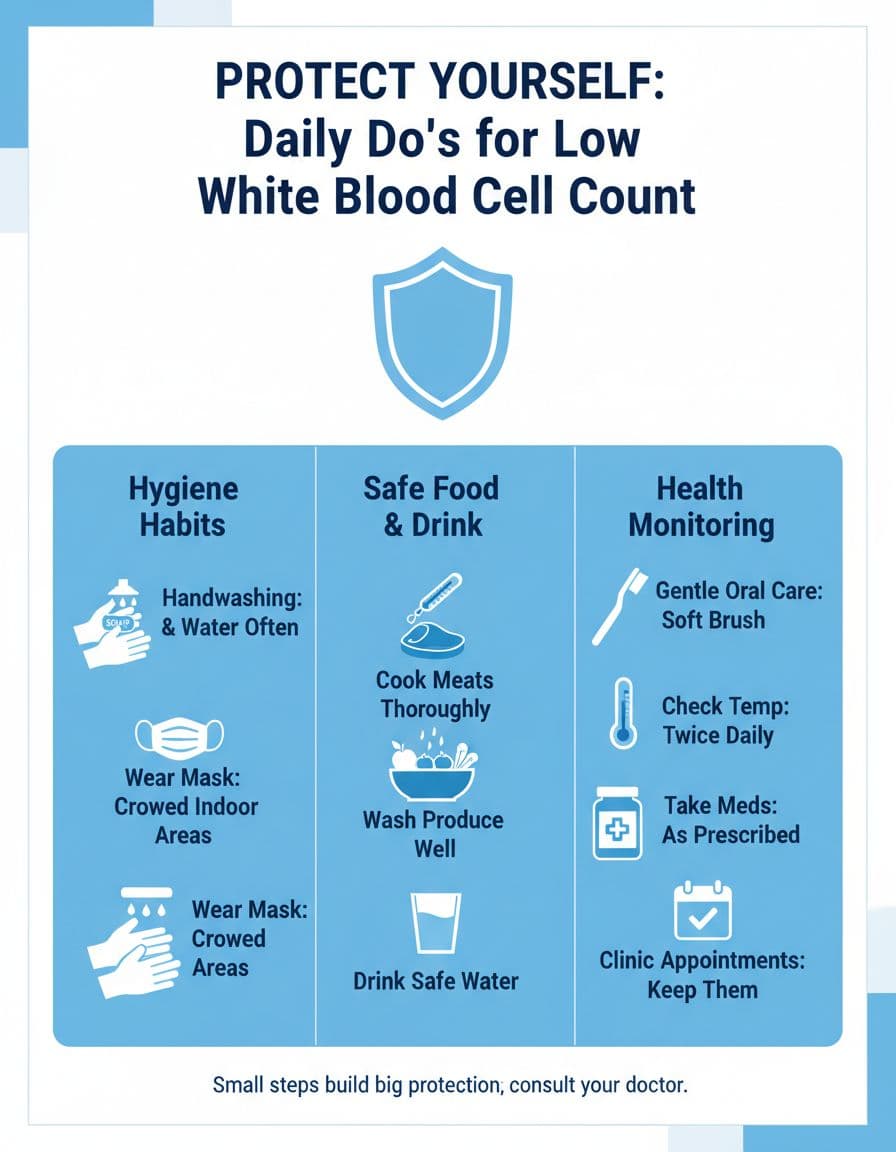

What to do (think: simple routines that add up)

When you’re worn down, “do more” isn’t helpful. A better goal is “do what works, consistently.”

Wash hands like it matters: Because it does. Wash after the bathroom, before eating, after being out in public, and after touching shared surfaces (carts, door handles, elevator buttons).

Cook food thoroughly and store it safely: Keep hot foods hot, cold foods cold, and don’t let leftovers linger. If you can’t remember how long it’s been in the fridge, toss it. It’s not waste, it’s wisdom.

Protect your mouth and skin: Use a soft toothbrush, be gentle with flossing if your team approves it, and keep lips from cracking. Tiny cuts and mouth sores can become entry points for infection.

Check your temperature the way your clinic wants you to: Use a working thermometer and know your clinic’s fever threshold and after-hours process. Keep the number saved. Put it on the fridge. Make it easy.

Take medications exactly as prescribed: That includes preventive antibiotics or growth factor shots, if you’ve been given them. If side effects are making adherence hard, tell the clinic. There are often fixes.

If you want another straightforward overview that matches what many oncology practices teach, this resource from the American Cancer Society is helpful: low white blood cell counts and neutropenia.

When to call the clinic (and when it can’t wait)

Calling can feel like you’re making a fuss. Many people hesitate. They don’t want to bother anyone, or they worry they’ll be told it’s nothing. But a low white blood cell count changes the rules. The clinic would rather hear from you early than meet you later in crisis.

A common urgent threshold is a fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher. Your team may use a different cutoff, so follow their instructions. If you hit the number they’ve given you, call right away, even at night.

Other symptoms that should prompt a call (or urgent evaluation) include:

| What you notice | Why it matters | What to do |

|---|---|---|

| Fever, chills, shaking | Infection can move fast in neutropenia | Call the clinic or after-hours line now |

| Shortness of breath, new cough, chest pain | Could be a lung infection or other urgent issue | Call now, seek emergency care if severe |

| Sore throat, mouth sores, new sinus pain | Early infection signs can be subtle | Call the clinic the same day |

| Burning or pain with urination | UTIs can escalate quickly | Call promptly, don’t wait it out |

| Redness, swelling, drainage, new pain at a wound or line site | Skin infections can spread | Call now |

| Uncontrolled vomiting or diarrhea | Dehydration and infection risk rise | Call for guidance the same day |

| New confusion, severe weakness, fainting | Can signal serious infection or dehydration | Get urgent help immediately |

One practical tip: don’t take fever-reducing medicine to “see if it goes away” before you’ve checked your temperature and contacted the clinic, unless your team has told you to do that. You want an accurate read, and you want clear instructions.

If you’d like a general checklist of warning signs from a major medical center, Mayo Clinic outlines when to seek care here: when to see a doctor for neutropenia.

Courage, in this moment, may look like picking up the phone. Not because you’re panicking, but because you’re paying attention.

Conclusion

A low white blood cell count can make the world feel sharper, louder, riskier. Still, you can meet it with steady choices: avoid high-risk exposures, keep a few daily habits, and call early when something feels off. If you’re in active Cancer treatment or in remission and monitoring labs, your goal isn’t perfection, it’s preparedness. Keep your clinic’s fever rules close, trust your instincts, and let your care team carry the weight with you.